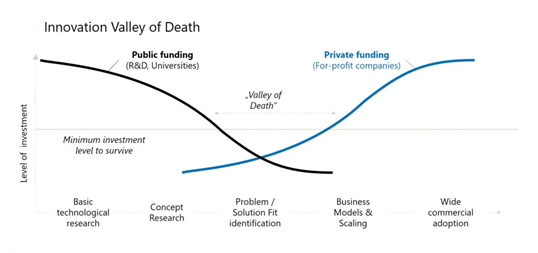

Every new industry or technology requires funding to survive, initially for research and development (R&D), developing processes and products, and then to scaling up to a viable business. A lot of the initial research is supported by public funding, which is subsequently replaced by private investments when the technology/product has been established and proven viable and scalable. However, in between these two extremes, there is a phase (known as the ‘innovation valley of death’; Figure 1) when public funds start to reduce (as solutions are being tested and problems identified) and private investments are low (due to uncertainties around the scaling up potential of the industry). When transitioning through this stage, progress slows down and some technologies/industries never come out of this ‘valley’.

Figure 1 – The “innovation valley of death” (https://www.ideatovalue.com/inno/nickskillicorn/2021/05/the-innovation-valley-of-death/)

The seaweed aquaculture industry in the UK and Europe is novel but has been growing in the last decade. This is demonstrated by the increase in the number of existing commercial seaweed farms, businesses and available seaweed-based products on the market and growing political support (https://marinescience.blog.gov.uk/2022/05/05/the-developing-uk-seaweed-industry/; Araújo et al. (2021) https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.626389). To unlock and harness the full potential of the industry, cultivation and production need to be upscaled and relevant markets for food and non-food applications need to be developed (https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/publications/communication-commission-towards-strong-and-sustainable-eu-algae-sector_en).

However, upscaling is hindered by multiple issues; some of them targeted by recent/current projects in the UK (e.g. Seaweed in East Anglia https://hethelinnovation.com/seaweed-in-east-anglia/; WWF UK’s Seaweed Solutions Programme; Project Madog https://projectmadoc.cymru/home/). Particularly, difficulties remain in obtaining licences for seaweed aquaculture and funding availability for prospective seaweed farmers. Furthermore, lack of standards on farming and products, technological barriers, and the need for social licence to operate and spatial planning are still important issues, common to the UK and Europe.

You may be wondering then, can the seaweed industry in the UK/Europe emerge from the ‘innovation valley of death’?

Back in June, I had the pleasure of attending the 13th Seagriculture Conference (https://seagriculture.eu/conference-program-2024/), in Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Figure 2), with two days of presentations, highlighting the main progress and challenges for the industry in the UK and Europe.

Figure 2. Landing in the Faroe Islands; seaweeds in Tórshavn port.

The ‘reality check’

Some of the issues and challenges in growing seaweed businesses to scale, highlighted by the presentations, included:

- The cost of farmed seaweeds per tonne is still too expensive compared to wild-harvest seaweed or to other crops (e.g. sugar kelp has a price per tonne 100 times higher than corn). This has implications for the economic viability of businesses.

- People do not eat (enough) seaweed in the UK or Europe, so it is key to identify other/additional uses for seaweed biomass (to ensure diversification of products and viability of businesses).

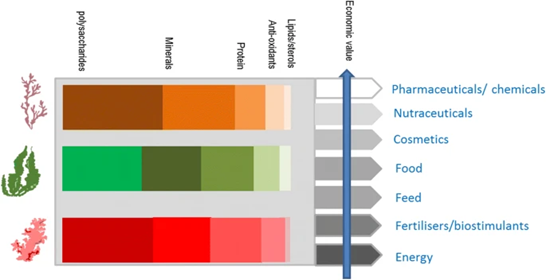

- There are a lot of valuable bioactives in seaweed (Figure 3); some are unique to seaweeds (e.g. fucoidan, alginate, ulvan, carrageenan, agars) and are not available in terrestrial crops. The concentration and quality of these bioactives can be variable. It is important to understand how environmental conditions, seaweed strains, time of harvest etc. affect the quantity and quality of these bioactives to ensure consistent quality of seaweed biomass;

- There is still a mismatch between seaweed producers and buyers/processing companies in terms of quantities produced/needed, species cultivated, and products, with the need to further develop links in the seaweed value chain;

- Ecosystem services provided by seaweed aquaculture, such as through carbon uptake and enhanced biodiversity, need to be quantified so they can be captured and incorporated into, for example, credit schemes, as well as communicated to consumers. The sector needs to be innovative but also trustworthy, not just from a consumer perspective but for the wider stakeholders including policymakers.

Figure 3. Range of interesting bioactives offered by seaweed, and potential uses versus their economic value (from Torres et al. 2019, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11157-019-09496-y)

It is not all doom and gloom!

There were also very encouraging highlights:

- Pilot farms in the North and Baltic Seas under EU-funded projects such as ULTFARM (https://ultfarms.eu/) and OLAMUR (https://olamur.eu/) are showing that seaweed can be successfully cultivated offshore in very energetic/exposed conditions (e.g. 11 m waves height) while co-located with offshore wind. Data from these pilots is key to demonstrating the feasibility of co-location and offshore cultivation, moving the innovation cycle to mature activities and providing evidence for decision making;

- There has been substantial progress towards the cultivation of dulse (Palmaria palmata); a highly flavoured, bacon-like tasting red seaweed which can be tricky to grow, offering potential for upscaling of this species;

- Innovative applications of seaweed include their use as an additive and probiotics for farmed animals; trials suggest they lead to improved animal health systems, for example in pigs, by improving their digestion and increasing their resistance to disease and therefore reducing the amount of feed needed and the need for antibiotics;

- Technological developments for mechanised harvest continue, with new farming methods, systems and harvesting machines which will be essential for scaling up cultivation;

- There are useful seaweed knowledge hubs (e.g. https://seaweedhub.extension.uconn.edu/, https://www.greenwave.org/hub) providing support to seaweed stakeholders throughout the value chain, which could be used as examples to develop a similar knowledge hub in the UK.

Returning to my initial question, I think the seaweed industry in the UK/EU is getting better and better equipped to emerge successfully from the “innovation valley of death”.

To support this journey Cefas’ work aims to provide the evidence to identify the appropriate siting of farms, to determine the impact of pollution and climate change on seaweed aquaculture, the effects of interactions between farms and the surrounding environment, and the potential role for the seaweed industry to support socio-economic needs while minimizing its environmental footprint.