Spurdog (also known as the spiny dogfish, scientific name Squalus acanthias) is a type of small shark found in oceans around the world. It can travel long distances and has been an important species for commercial fishing in the past.

However, the number of spurdog in the Northeast Atlantic (the part of the Atlantic Ocean near Europe) dropped significantly in the early 2000’s compared to how many there were in the 1950s and 60s. Because of this sharp decline, governments introduced strict fishing rules to help the population recover.

From 2010 to 2022, fishermen were not allowed to catch spurdog on purpose, and the total amount of spurdog that could be legally caught, called the Total Allowable Catch (TAC), was set to zero. The only exception was a small amount that could be kept if the fish were accidentally caught while fishing for other species. This was part of what’s called a Bycatch Avoidance Scheme, which is a program designed to reduce the number of unwanted fish caught by accident (called bycatch).

In 2017, spurdog was officially listed as a prohibited species, which meant it was illegal to keep or land any spurdog, even if caught by accident.

But in 2022, the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), a group of scientists that gives advice on ocean health and fish stocks, said that spurdog populations had improved enough to allow limited fishing again. So, for 2023 and 2024, a controlled amount of spurdog fishing (a TAC) was allowed, and the species was no longer officially prohibited.

Even with this change, a careful, precautionary approach was still needed to protect the population. One key measure was that any spurdog longer than 100cm must still be protected. These larger sharks are usually females that can produce many pups, so protecting them helps the population stay healthy and grow.

Cefas research project

In April 2023, the UK government's Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), asked scientists at Cefas to carry out a research project on spurdog. The goal was to help manage the spurdog, a species that was fully protected until 2023 but is now allowed to be caught in limited amounts under new commercial fishing rules. Even though fishing is now allowed, the larger spurdog, which are usually females that can produce the most and biggest pups, are still protected and cannot be landed.

As part of this project, Cefas is working on several key areas:

- Tracking how many spurdog are being caught, including both those kept and those thrown back (called discards). They’re also asking the fishing industry to record whether the discarded fish are still alive.

- Checking whether the rules protecting larger spurdog are working. For example: Are the bans on landing big individuals stopping people from targeting the most fertile females? And is the 100cm size limit the right one for protection?

- Looking into other possible rules that could be added or used instead of the size-based protection, to make sure the spurdog population stays healthy in the long term. Any future changes to how spurdog are managed will depend on having strong scientific evidence to back them up.

Our Spurdog video will explain more.

How are we doing this?

Working with the Fishing Industry and Other Stakeholders

We’re speaking with a wide range of people who are involved with or affected by spurdog fishing. This includes local and national organisations like UK fishing groups, scientists, conservation groups such as the Shark Trust, and recreational fishing representatives like the Angling Trust. We want to understand their concerns, expectations, and how they’re responding to the return of commercial spurdog fishing.

We’re also holding national project meetings to share progress, discuss the latest research, and make sure everyone involved is on the same page.

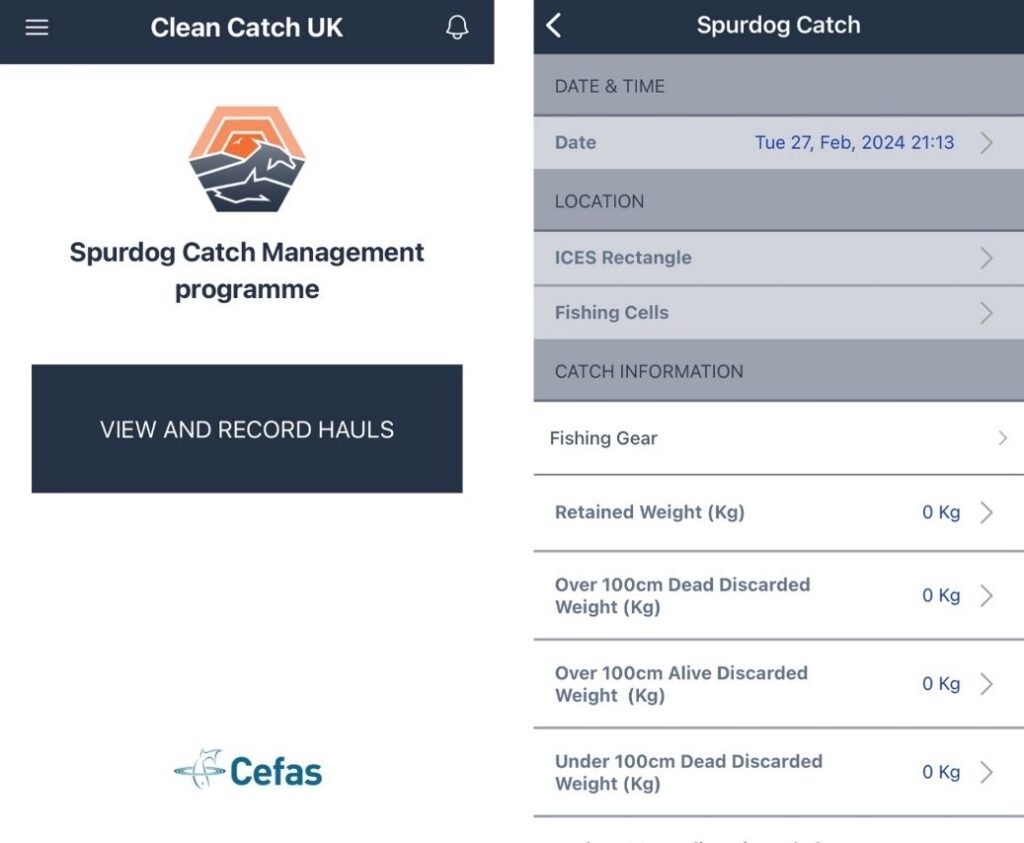

At the quayside, we’ve been talking directly with skippers to find out if they plan to change how they fish now that spurdog can be caught again. We’ve also asked whether they’d be willing to voluntarily report their catches, including how much spurdog they keep, and how much they discard, whether dead or alive, using the Clean Catch app.

By talking to those involved in the onshore industry such as processors and sellers of spurdog, we have been exploring the relationship between current market conditions for spurdog, and the fisheries management measures introduced in April 2023.

Tracking What’s Being Caught

We’ve set up a baseline, a picture of what spurdog catches and discards looked like before the fishing rules changed (from 2016 to 2022). Most of that data came from:

- The Cefas observer programme, where trained scientists go on board fishing vessels to record what’s caught

- Industry data collected during the bycatch avoidance scheme

These sources give us some of the best available information, and they continue to be essential for understanding how things are changing now that spurdog fishing is allowed again.

We’re using:

- UK landings data (what fishers report in their logbooks)

- Data from the Cefas observer programme

- Vessel tracking data (called Vessel Monitoring System or VMS)

This helps us see where and when spurdog are being caught, and how that compares to previous years.

We’re also collecting information on recreational catches, to understand how important spurdog is to the sector.

Looking at What Happens After Spurdog Are Caught and Released

We’ve reviewed previous scientific studies to understand how many spurdog survive after being caught and then released, both right away and over time.

We combined this with:

- Data from the bycatch avoidance scheme, including fishers’ own reports on whether discarded spurdog were alive or dead

- Tagging studies, where fish are tagged and tracked after release to see if they survive

We’re also figuring out what extra information is needed to improve these estimates and make them more reliable.

Improving the App and Data Collection

The information that fishers shared during the bycatch avoidance scheme has turned out to be some of the most valuable data we have. It helped us understand spurdog catches during the time when fishing was banned and allowed us to see how fishing patterns changed once new rules came in.

This data was also critical for understanding how many spurdog survive after being discarded, especially for different types of fishing methods like gillnetting and trawling.

Now, with the Clean Catch app, fishers can continue to submit valuable data. The app makes it easy to record details about:

- The number of spurdog caught

- Whether they were kept or discarded

- If discarded, whether they were alive or dead

- Whether the fish were over or under 100 cm in length

This data is held by the app developers but can be accessed by Cefas to improve our understanding of how well spurdog survive after being released, especially for the bigger, protected individuals and how the fishery is changing overall.

If you are a fisherman and want to submit data on your spurdog catches, watch this video to find out how to download the app and use it: