By John Pinnegar, Director of the International Marine Climate Change Centre, Cefas and Caroline Rowland, Head of Oceans, Cryosphere and Dangerous Climate Change, Met Office.

In 2023 and 2024, global air temperatures reached unprecedented levels, with 2023 being officially the hottest year on record and 2024 expected to be hotter still. The ocean, which absorbs around 90% of this excess heat, is also experiencing significant warming (Fig 1). This year, due to a combination of long-term climate change and short-term climate variability due to El Niño, global sea surface temperatures (SSTs) hit record highs. Decades of sustained ocean warming have led to an increase in both the frequency and severity of marine heatwaves—periods of unusually high sea temperatures for 5 days or more that can have devastating effects on marine biodiversity.

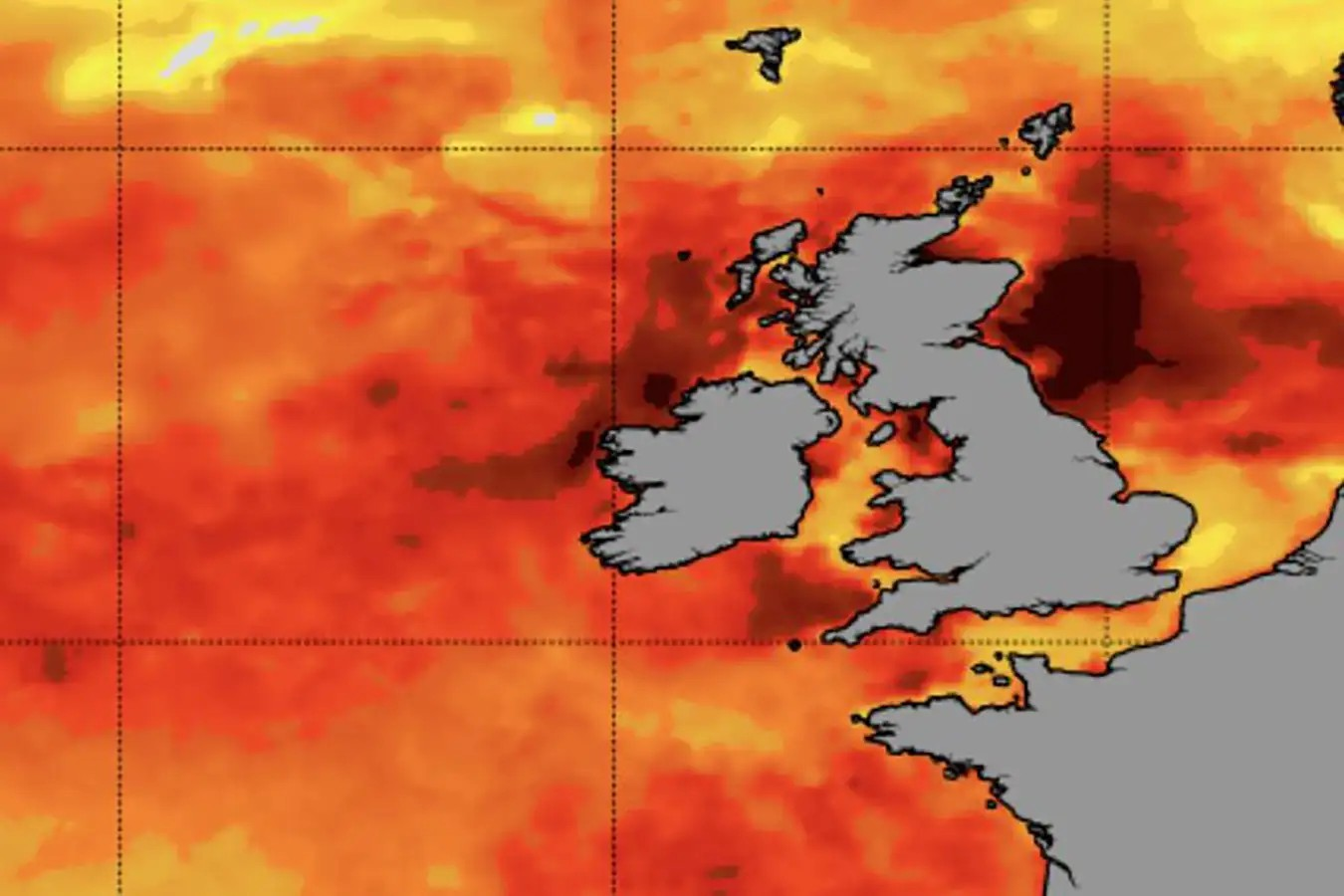

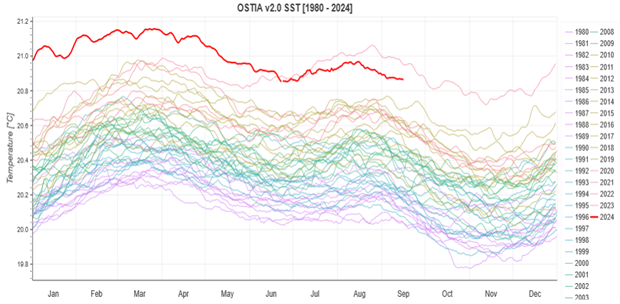

Over the past 40 years sea temperatures in the UK have risen by around 1°C, and overall the number of marine heatwaves has increased by around four per year in recent decades. In June 2023, the seas around the UK experienced a marine heatwave, with sea surface temperatures reaching their highest levels for June since records began in 1850—an event of such intensity rarely seen outside the tropics and the Mediterranean (Fig 2).

Like heatwaves on land, marine heatwaves can have serious impacts on the health of marine wildlife, on ecosystems and subsequently, on the economy. However, the impacts in UK waters such as those experienced during the UK 2023 heatwave, can be difficult to predict, monitor and quantify. As UK waters continue to warm, and the frequency of marine heatwaves is predicted to increase, the distinction between extreme events, and long-term warming becomes increasingly blurred. Temperatures that we now consider as marine heatwaves are likely to become the new norm in future years.

For scientists working to understand marine heatwaves in the UK, the challenge is to keep pace. It is critical to provide policymakers and stakeholders with the necessary information to make informed decisions for both people and the environment. In response, the Met Office and Cefas have joined forces recognising that a collective approach —leveraging the complementary capabilities of multiple organisations—is essential to understand both the weather and climate drivers of marine heatwaves and their impacts on the health of our seas.

UK scientific capability in predicting and monitoring marine heatwaves

The UK has developed strong scientific capabilities for predicting and monitoring marine heatwaves, involving key UK government bodies, such as the Met Office, Cefas, the Marine Directorate of Scottish government and the Food Standards Agency (FSA), alongside the UK’s marine science and operational oceanography community. These organisations play an important role in the monitoring and prediction of ocean temperatures, marine heatwaves and their effects on ocean health and biodiversity.

The Met Office, the UK government’s national meteorological and climate science agency, provides ocean forecast services and resources from days, months to years ahead. These services include observed climatology and SST analyses derived from satellite and in-situ observations, combined with model-based global and regional ocean forecasts. The OSTIA (Operational Sea Surface Temperature and Sea Ice Analysis) system, developed in the 1980s, monitors SST’s globally, helping to track marine heatwaves worldwide.

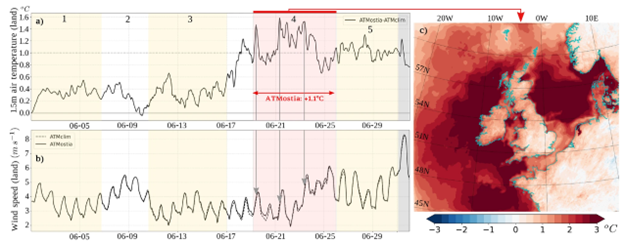

In addition, the Met Office integrates satellite data and data collected around the UK’s shelf seas by ships, buoys, floats and gliders into two different regional modelling systems. One generates 6-day forecasts with a spatial resolution of 1.5km, and the other forecasts at 7km resolution. These models also predict oxygen, carbon dioxide and pH levels, nutrient availability and markers of phytoplankton to understand the health of our seas. A new innovative km-scale atmosphere-ocean-wave-biogeochemistry coupled model is also in development. This will allow longer range forecasting to capture whole system changes to our marine environment. These models, datasets and observations have been instrumental in helping to understand the unprecedented June 2023 marine heatwave.

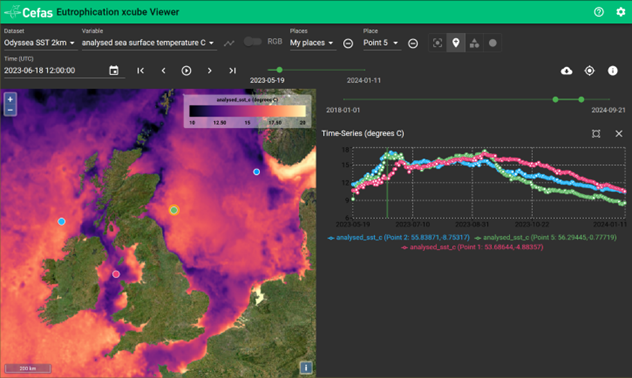

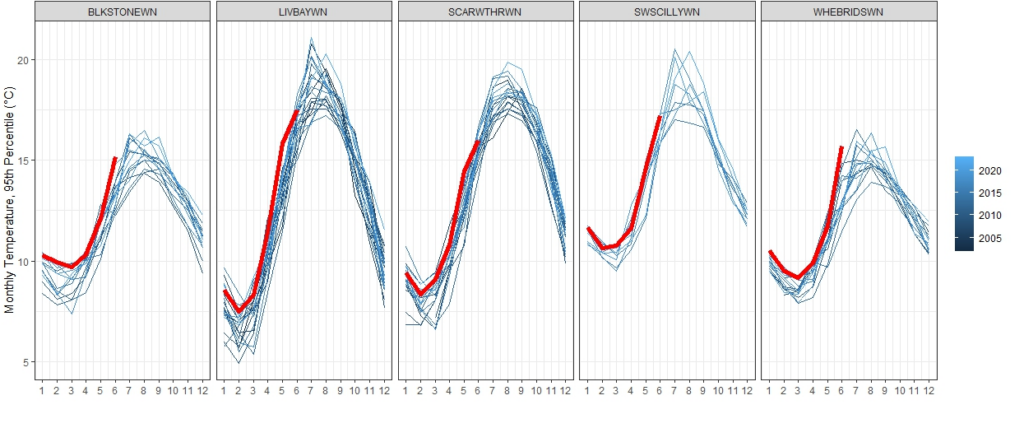

Cefas, the UK government’s leading marine science agency, conducts research, and generates evidence and advice on the health of the UK’s waters. Through its network of state-of-the-art autonomous monitoring buoys, Cefas collects real-time data on SSTs, which feeds into Met Office forecasts and long-term reporting. In August 2022, Cefas' WaveNet buoys recorded (Fig 4) some of the highest sustained seawater temperatures ever recorded around the British Isles, exceeding 21°C off the Thames Estuary. This real-time data is integrated into Cefas’ datacube viewer (Fig 3) which in 2023 allowed scientists and forecasters to track the development and spatial spread of the UK marine heatwave over time. Technological advances in data collection now allow thousands of sea temperature measurements to be gathered every minute—a significant leap from the days when scientists recorded only a few measurements each year using pen and paper!

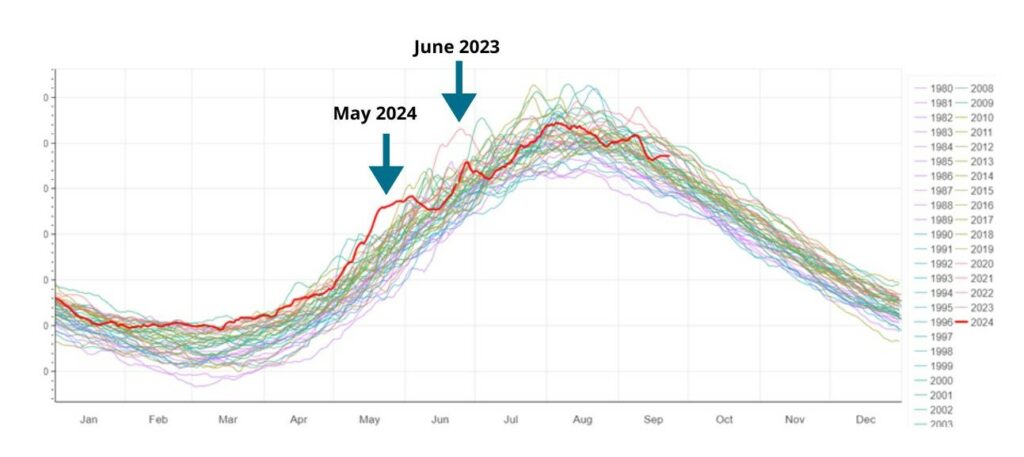

Despite these advances, the drivers, impacts and risks associated with marine heatwaves in the UK remain relatively underexplored. Recent analysis by the Met Office of the unprecedented June 2023 marine heatwave has provided valuable insights into the weather patterns and physical drivers that caused this event and also the subsequent impacts on inland UK temperatures (Fig 5). This analysis was also used to understand the most recent May 2024 marine heatwave, which found that both marine heatwaves contributed to breaking UK land temperature records by a large margin. Further research is ongoing to refine which weather patterns are associated with marine heatwaves around the UK, as well as the biological impacts.

Challenges of understanding marine heatwaves in the UK

Marine heatwaves in the UK are generally short-lived, lasting between 5-15 days due to our highly variable climate. They often occur during hot, dry and windless conditions that make it difficult for warmer water in the upper layers of the ocean to mix with cooler water below. Marine heatwaves typically end when stronger winds release the heat into the atmosphere or redistribute it into the ocean. Certain areas, like the English Channel and parts of the Irish Sea are less prone to surface based marine heatwaves due to strong tidal currents.

Between 1993 and 2019, marine heatwaves occurred almost yearly around the UK, though their biological impacts remain poorly understood. Some of the main challenges in understanding marine heatwaves is generating accurate and consistent ‘in situ’ data. While gliders deployed by the Plymouth Marine Laboratory and the Scottish Association for Marine Science during the 2023 heatwave were at the right place at the right time, allowing real time monitoring of the event and providing valuable data into what was happening beneath the surface, large areas of the UK’s 12,000 km of coastline do not have autonomous monitoring systems. Improved data collection and increased monitoring are vital to enable scientists to better understand complex ecosystems and physical properties (e.g. temperature) in UK waters allowing for better identification of marine heatwaves and their impacts. Also, a more responsive, real-time monitoring system, which could be triggered as a marine heatwave occurs, could significantly enhance our understanding of future events.

Long-term monitoring and data collection from coastal regions throughout the UK, including observations at depth, also remain a challenge. Initiatives like the Western Channel Observatory, jointly maintained by Plymouth Marine Laboratory, have helped bridge this gap by providing over 100 years of data on long-term changes in ocean heat content at depth. However, more long-term data is needed to better understand marine heatwaves in their historical context and track their development and impacts over time. Additionally, better coordination, increased data sharing across UK regions, and increased investment in research are crucial to gaining a deeper understanding of marine extremes.

Understanding the impacts of marine heatwaves on fisheries and biodiversity

Globally marine heatwaves are significant stressors to marine environments. They can disrupt the growth rate and reproductive systems of marine organisms, cause metabolic disruption and disease leading to mass mortality events, impact ecosystem services and cause large-scale changes to species density and distribution. While some of the best-known impacts include well-publicised coral bleaching events in the tropics, serious effects can also be seen much closer to home.

For example, marine heatwaves have been linked to harmful algal toxic blooms in UK waters and Cefas works with food safety agencies like the FSA and Food Standards Scotland to ensure public safety through biotoxin monitoring (the results are published here). Another lesser-known impact is their role in increasing the risk of infectious diseases dangerous to humans. During the 2018 UK marine heatwave, Cefas found increased levels of pathogenic Vibrio species, both in the water and in shellfish from several sites along the southwest coast of the UK. New research by Cefas shows that pathogens causing serious threat to health, such as Vibrio vulnificus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio cholerae, can all be found in UK waters and present an emerging threat to public health here and around the world.

Despite a wide range of impacts, there are significant gaps in understanding the effects of marine heatwaves on marine species, ecosystems, and the fisheries they support. Limited data on the real-time impacts of heatwaves, combined with the potential lag in the appearance of some biological and ecological effects (which sometimes become evident only a few years later) adds to the uncertainty. The effects on species can also be complex and mixed, with both ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ implications for species and the people that depend on them.

For example, Cefas, alongside the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) and the Met Office, was the first to identify a link between extreme temperature events and the landings of key fish and shellfish stocks in the North Sea; showing that catches of sole, European lobster and sea bass increased five years after a heatwave event, whereas catches of red mullet decreased. Long-term warming due to climate change has also been linked to an increase in habitat suitability for certain UK marine species, with localised decreases for others.

While the impacts of recent marine heatwaves may still materialise, new evidence of the effects of warming seas is emerging. For example, recent research by the Kent & Essex Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (IFCA) and the University of Essex has revealed that mass mortalities of whelk in the Thames Estuary in August 2022 coincided with record temperatures measured by Cefas. Interestingly no similar mass mortality events of whelks were reported during the 2023 heatwave.

As scientists, our challenge is to understand the extent to which these phenomena are driven primarily by marine heatwaves or by other environmental or human-induced factors, such as pollution or disease. A whole systems-based approach, where data from diverse sources is analysed and interpreted, including the use of new approaches to pattern recognition (including AI) will be key. Future collaboration and research with partners will be vital to understand these trends. This knowledge will be essential to ensure the fishing industry, consumers and stakeholders continue to prepare and adapt to a changing climate.

Improving the UK’s response to marine heatwaves in the future

As marine heatwaves become more frequent and intense, how can scientists and policymakers be better prepared?

At a recent workshop held at the NOC, Southampton, experts from across the UK met to identify important research gaps (‘40 key questions’) to better understand UK marine heatwaves. The workshop also highlighted the need to generate and communicate the latest data and advice to support policymakers in understanding and responding to marine heatwaves. The Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership (MMCIP), for example, which plays an important role in bringing together the scientific evidence for climate change impacts in UK seas, is likely to place a greater focus on marine heatwaves and their impacts on people and the environment going forward

A significant challenge is also the lack of a central coordinating body for marine heatwave monitoring in the UK. Such a body could provide early warnings, coordinate sampling and data collection, and offer technical expertise in response to specific incidents. A marine heatwave monitoring system, such as the prototype currently under development by the Met Office, could serve as a valuable ‘early warning’ tool for alerting stakeholders to marine heatwaves and their potential impacts. How useful such a system would be and how it could be used to respond and adapt to marine heatwaves are key questions to be explored.

Finally, as the distinction between marine heatwaves and long-term warming becomes increasingly blurred, the scientific community may need to rethink how these events are defined and measured. Will average temperatures continue to rise, necessitating new benchmarks for heatwaves? Would impact-based criteria, such as those used for land-based heatwaves, be more useful in defining marine heatwaves? These questions underscore the importance for Met Office, Cefas and partners to continue ongoing research and collaboration to prepare for a future where marine heatwaves are an ever-present challenge.