Offshore wind developments exist among other marine activities, how do we balance them and is compensation suitable in order to meet net zero goals?

The UK’s marine area is becoming increasingly busy with multiple users from different sectors all making use of our marine resources to fish, source construction material, maintain navigation channels for trade, and generate energy. With the recognition of the current climate emergency there is now greater focus on generating energy from renewable sources to meet our net zero goals – this includes a greater role for offshore renewable energy developments. But how do we balance the benefits these different activities provide and their impacts on the environment?

The UK’s 25 Year Environment Plan commits to leave the environment in a better state than we found it. Sometimes this is done by protecting key habitats and species and ecosystem services with the introduction of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) which control human activities in certain areas.

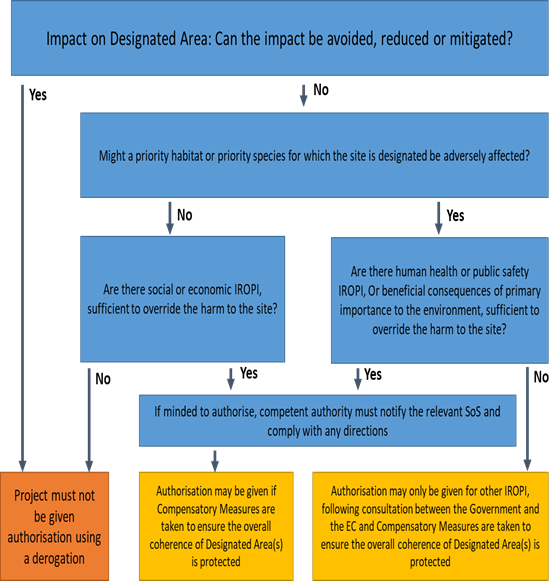

Wherever possible, developments should aim to avoid negative impacts on the environment. Where these are not avoidable, these impacts should be reduced or mitigated as far as possible. However, with so many environmental, social and economic factors to consider, some large national infrastructure plans, even after considerable attempts to avoid, reduce or mitigate, cannot eliminate all negative impacts. Where developments, such as offshore wind farms, have the potential to impact protected sites, they may still be able to proceed provided that certain tests can be met. These tests include that there are no suitable alternative options and that there are Imperative Reasons of Overriding Interest (IROPI) in line with the requirements of The Conservation of Species and Habitats Regulations 2017 or that the benefit to the public of proceeding with the development clearly outweighs the risk of damage to the environment in line with the requirements of the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009.

In these cases, regulators may apply derogations to the legislation to approve the project on the basis of the societal benefits, but when doing so “compensatory measures” need to be secured to address the environmental impacts. These compensatory measures in the UK may be used to create new habitats including mudflats, saltmarsh, shingle or sand dunes, glacial cobble skear and reedbeds. In doing so they seek to offer protection and enhance vulnerable features and species as much as possible. Any compensatory measures must be sufficient to address any loss or damage within a site and ensure that the integrity of the national site network is maintained.

Compensatory measures must be carefully considered, so Defra commissioned Cefas to lead a project to review measures already used nationally and internationally and evaluate how applicable they are to UK offshore developments.

The need

Defra have now published the review of the use of compensatory measures and their applicability to UK Offshore developments. This project is one of the first comprehensive reviews of compensatory measures worldwide and how they might apply to offshore wind farm developments in the UK.

The findings increase our understanding of this complex problem and provides suggestions for managing the co-existence of human activities in our increasingly important marine space, balancing localised and wider impacts for people, environments and the wildlife they support. From this review, key points were identified and a set of best practice principles for compensatory measures in the UK were suggested.

The project

The project brought together expertise and knowledge from Cefas, Natural England and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC). The project aimed to define, highlight and review key areas for considerations on the use and application of compensatory measures to UK offshore developments.

The report gives a common definition of compensatory measures and reviewed both UK and international case studies where there was a need for derogation in the legislation for either UK or EU marine protected areas.

If used, compensatory measures must be well designed and monitored. Consideration was given to the assessment and ‘success criteria’ used for compensatory measures, and for demonstrating compliance with legal obligations for projects where a protected feature is impacted. In this way the review looked at how we can ensure such measures had the intended effect.

The findings

The compensatory measures observed for marine projects in the UK were predominantly habitat creation associated with managed realignment (in 11 of the 17 case studies). This means creating or adapting habitats in a different location and helping species to relocate as a substitute for the habitat lost to the development. Issues identified with this approach included difficulties in obtaining information, measuring success and developers facing barriers or difficulties with legal compliance. The types of habitat created included mudflats, salt marsh, shingle sand, dunes, glacial cobble skear and reedbeds. However, some habitats’ ability to function in the long term were questionable (for example, low-level mudflat naturally accreting to saltmarsh) or difficult to quantify due to natural variation.

Comparing the results of the UK and non-UK case studies, and considering the principles of transferability, compensatory measures used outside of the UK, did not differ considerably from those used in the UK. Measures like habitat restoration abroad were undertaken much as they are in the UK. However, notably the regulatory framework in Finland provides a mandate for compensatory measures for sites not covered by the EU Habitats Directive, providing wider protection to vulnerable sites and species considered to be of high environmental importance.

What does it mean?

Compensatory measures are applied following consideration of many different impacts on the marine environment and the life it supports, and the benefits provided by development on which society relies. Where it is not possible to avoid, reduce or mitigate these impacts in line with the core legislative requirements, then following a derogations process, compensatory measures will have to be applied. Decision-makers can only approve such measures if operators can demonstrate that all other options have been exhausted.

However, this must be done with the right evidence and analysis. Current barriers to the success of compensatory measures included knowledge gaps and a lack of understanding of baselines or receptors for offshore areas. Offshore receptors such as marine mammals and migratory fish that may not use habitats in the same way might require different measures for loss of habitat dependent on the receptor.

Designing and implementing targeted and appropriate compensatory measures, however, did not guarantee effectiveness. The review showed that this was critically dependent on the management of the measure. For compensatory measures to be effective there needs to be regular constructive communications between competent authorities, assessment authorities and the proponents of the plan or project. Where there was a framework with clear objectives and target values provided in regard to the site’s conservation objectives, success was easier to observe.

The timescale to reach success and consequently for monitoring measures was dependent on the type of measures used and the rate of success was different for each project and largely due to the physical, geographical, and biological context applied.

Some schemes originally determined as successful that could be or are expected to be added to the network of conservation areas, are still waiting to be adopted into conservation designations, and the indication of their contribution to the coherence of the conservation networks remain undefined.

To be transferable and allow for improvement, reporting of these plans and projects needs to be consistent and easily accessible. In some examples, strong regulator/stakeholder steering committees for monitoring provided a basis for measures to deliver good ecological outcomes and provided opportunities for adaptive management and sign off.

For plans and projects where there is difficulty and uncertainty remaining, adopting a precautionary approach will be necessary to try to balance demonstration of “no reasonable doubt”, and therefore potentially requires over-compensating.

These best practice principles are intended to be used and added to by stakeholders as part of an iterative management framework, building on research evidence and evaluation to ensure that where compensatory measures are applied, they are appropriate and well-designed to protect wildlife and habitats.

To read the document, click here.