Climate change is altering the distribution of many marine fish species, with widespread impacts on biodiversity, with the potential to jeopardise world food security. Most studies to date focus on how commercially exploited fish species will be affected by climate change without consideration for different life stages across different species. Body size plays an important role in how fish interact with their prey and is therefore a useful ‘super trait’ to understand current and future changes to the structure of marine food webs. Climate change is expected to favour smaller fish, who need and expend less energy in response to warming compared with larger fish. Categorising fish using their species identity and body size into ‘feeding guilds’ associated with different prey is therefore useful to understand how marine ecosystems could change in future in response to climate change.

In this blog, Murray Thompson, Principal Marine Conservation Scientist, and Elena Couce, Senior Quantitative Ecologist at Cefas, discuss their recent paper featured in the journal of Global Change Biology which looks at how climate change will affect the habitat suitability of marine fish species across a range of body sizes and belonging to different feeding guilds in the northeast Atlantic shelf seas.

How is this paper helping us to understand the impacts of climate change on food web

Murray: Many studies predict changes in the way fish species are distributed and community size composition in response to climate change, yet few have demonstrated how these changes will be distributed across marine food webs. In this study, we looked at how climate change will affect the habitat suitability of marine fish species across a range of body sizes and belonging to different feeding guilds, each with different habitat and feeding requirements in the northeast Atlantic shelf seas. We found that that species richness will change at different rates and even in different directions across the food web over large areas. We therefore expect quite big and complex changes in the ecosystem functioning of marine ecosystems, as changes in the distributions of species performing critical ecosystem functions fundamentally alters how and where energy moves through the system. Importantly, our results show that regional increases in community-wide species richness can mask the loss of species that are critical to maintaining ecosystem functioning. These changes add to the evidence base that world food security could be greatly impacted by climate change.

What types of data did it look at?

Murray: This work draws on data from internationally coordinated fisheries independent surveys for fish stocks. We also looked at fish stomach contents data to position fish within feeding guilds based on their size and species identity.

Elena: In terms of climate data, we used climate projections available from Copernicus, among other environmental data layers, such as seabed substrate composition that were kept constant for the future.

What type of changes might we expect to see in terms of the distribution of certain fish species as a result of climate change?

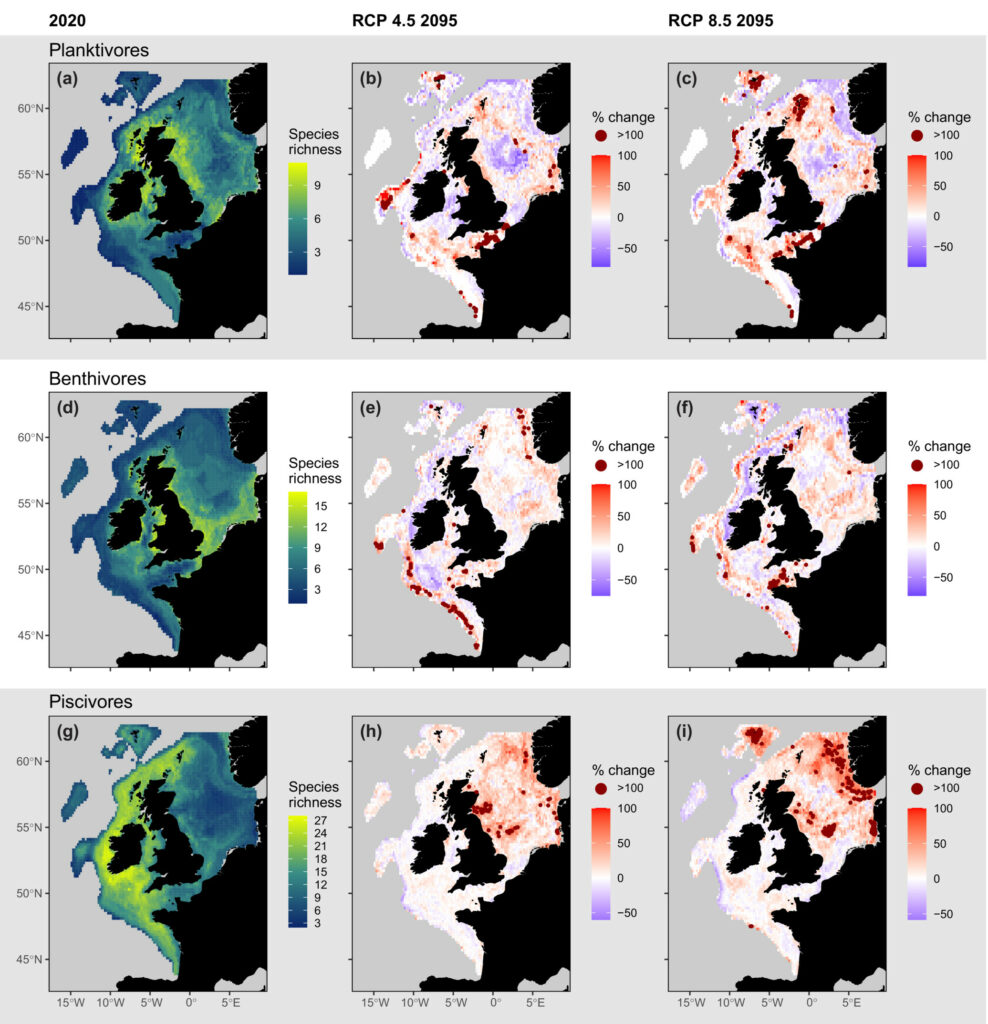

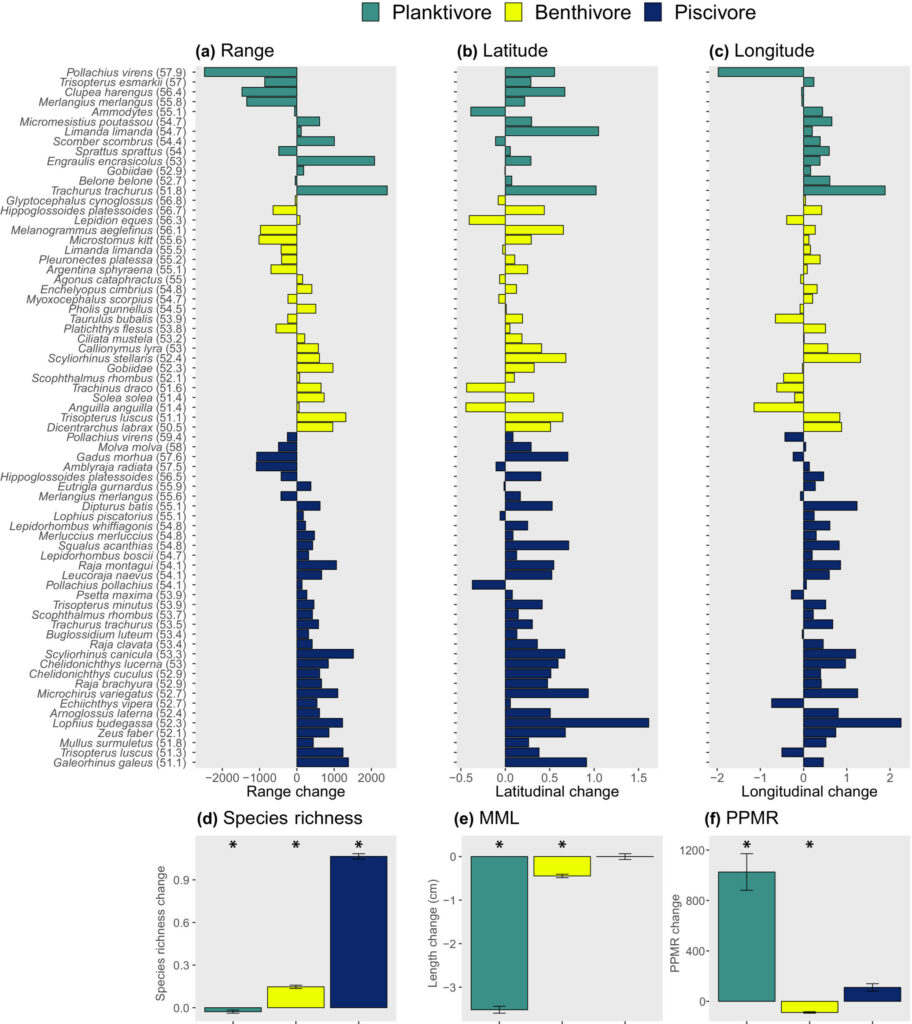

Elena: There have been some interesting findings. For example, we might expect a species whose habitat range was increasing to simply occupy the space left by species within the same guild who faced a decrease in range (Figures 3 and 4). Instead, those increasing in range are predicted to prosper in other areas of the ecosystem, with some regions experiencing contrasting directions of change in species richness across the food web. These changes will deplete species in some areas where they perform critical ecosystem functions (e.g. planktivorous herring(Clupea harengus) and Norway pout (Trisopterus esmarkii), while bolstering others (e.g. planktivorous anchovy (Engraulis encrasicholus) and Atlantic horse mackerel(Trachurus trachurus); Figure 4), and thus fundamentally alter how and where energy moves through the ecosystem.

Figure 3:

Figure:4

You mentioned that regional increases in community-wide species richness could have the potential to ‘mask’ or hide the loss of species that are critical to maintaining ecosystem functioning’. Could you explain more?

Murray: If we were to look at species richness for all fish, then we would see an increase across much of the study area driven by an increase in more southerly distributed fish species, which might appear like a positive thing. However, when we categorise fish into food web levels which utilise different prey, we see that increases are largely occurring higher in the food web, in the piscivore guild which prey on other fish. Changes in the species richness of planktivores (fish that feed on zooplankton) and benthivores (fish that prey on organisms dwelling on the seafloor) is much more varied, with large areas showing declines. These fish lower in the food web are key pathways for energy, e.g. planktivores eat plankton before being eaten themselves by piscivores and other top-predators. If the species richness is compromised in these lower guilds, this could have widespread impacts on their predators (piscivores, mammals, birds), their prey (plankton, benthos), and disrupt ecosystem functioning.

How can the fishing industry and policy makers use this paper to support climate adaptation/management efforts?

Elena: The paper can help fisheries understand the potential impacts of climate change on fish stocks and therefore what we might do to ensure future sustainability. Typically, fish distributions are moving poleward so that could mean some species move out of range of UK fleets, or at least to areas that are more challenging to exploit, but also other species will move in. There are noteworthy areas of climate refugia including the deeper areas of the North Sea or more stable areas such as Atlantic facing coastal waters of the UK and Ireland. These areas could be where conservation efforts e.g. marine protected areas, have most impact because they cover areas of high biodiversity into the future. Areas which are predicted to change most in response to climate change, such as the central North Sea where planktivore species richness is predicted to decrease and piscivores increase, may also benefit from protections to help alleviate other pressures that could compound changes.

Murray: Put simply, big fish eat little fish, but how big the big fish is compared to its prey affects the rate energy can flow across the food web. Particularly big fish eating particularly small prey (an extreme example being baleen whales feeding on plankton) can help conserve and stabilise food webs (by helping to avoid extreme increases and decreases in population numbers). However, we predict larger fish species which prey on relatively small prey will decrease in future in each feeding guild. This could mean that the food web becomes less stable and less resilient to other stressors, such as fishing and climate change. Conserving bigger fish which tend to prey on particularly small organisms should therefore be a priority - these are typically larger, older individuals of a species that continue to consume small prey as they grow, e.g. herring and Atlantic mackerel.

What are the next stages of the research?

Murray: This study did not look at other human pressures on food webs, such as from fishing, so going forward we are looking at such impacts and quantifying change in biomass and energy flux. For example, we aim to: i) quantify changes in the biomass of different guilds; ii) the amount of energy they demand from their prey; iii) and supply to their predators under different fishing scenarios and in light of climate change – but there are many hurdles before we get there! A key challenge will be to understand how fishers will respond to climate change. We are also looking at how different fishing practices affect feeding guild structure (diversity and biomass) using dynamical models to understand what might be sustainable versus unsustainable fishing practices – and whether a sweet spot exists, what we call an ‘ecologically safe space’ that conserves biodiversity, provides sustainable fisheries yields where risk of species loss is minimised.