SMARTFISH H2020 is an international research project which aims to develop, test, and promote a suite of high-tech systems for the EU fishing sector. The goal is to optimise resource efficiency, improve automatic data collection for fish stock assessment, provide evidence of compliance with fishery regulations and reduce the ecological impact of the industry. Cefas Principal Scientist and Project Lead, Tom Catchpole, reflects here on research outcomes achieved by Cefas scientists, industry, and research partners.

Cefas has been working since 2018 with the commercial fishing sector, including UK-based demersal mixed-species beam trawlers, otter trawlers and gill netters in the southern North Sea and Celtic Sea regions to develop and demonstrate innovative SMARTFISH technologies. This includes novel fishing gears to avoid unwanted catches, automatic catch data collection and data sharing tools, with the aim to enhance scientific advice and better inform decision-making by fisheries managers.

Innovations to quantify catches using images

Two SMARTFISH innovations utilise the rapid advances in camera technology, machine learning, and artificial intelligence to perform tasks such as image classification and object recognition, allowing scientists to gather data on commercial fish catches. Working with the skipper and crews of mixed-species trawlers in the southwest of England, and the University of East Anglia’s (UEA) School of Computing Sciences team, CatchMonitor has been developed to automatically identify and count fish during the catch sorting process using video footage from onboard cameras. Researchers are also working in collaboration with small-scale fishers who use pots to catch crabs and lobsters in the English Channel and southern North Sea, and with Bangor University to develop the CatchCam system that also collects detailed data on catches.

Why do we need better catch data?

There are essential benefits to producing better catch data for both the commercial fishing and research sector. For fishers, detailed catch information enables them to optimise the use of the fish quotas available to them, thus improving the economic efficiency of their businesses. This also means unintended catches can be reduced, in turn minimising the fishing pressure and ecosystem impacts. For scientists, improved catch data means more confidence in the advice provided on the sustainable levels of fishing and the ability to inform decisions and policy. For example, data on European crab and lobster stocks are limited; this restricts the management options for the sustainable exploitation of these stocks. Improved catch information can also inform fisheries managers on levels of compliance with regulations and can be used as the basis for developing effective new management measures to support stock sustainability.

Innovations to reduce unwanted catches

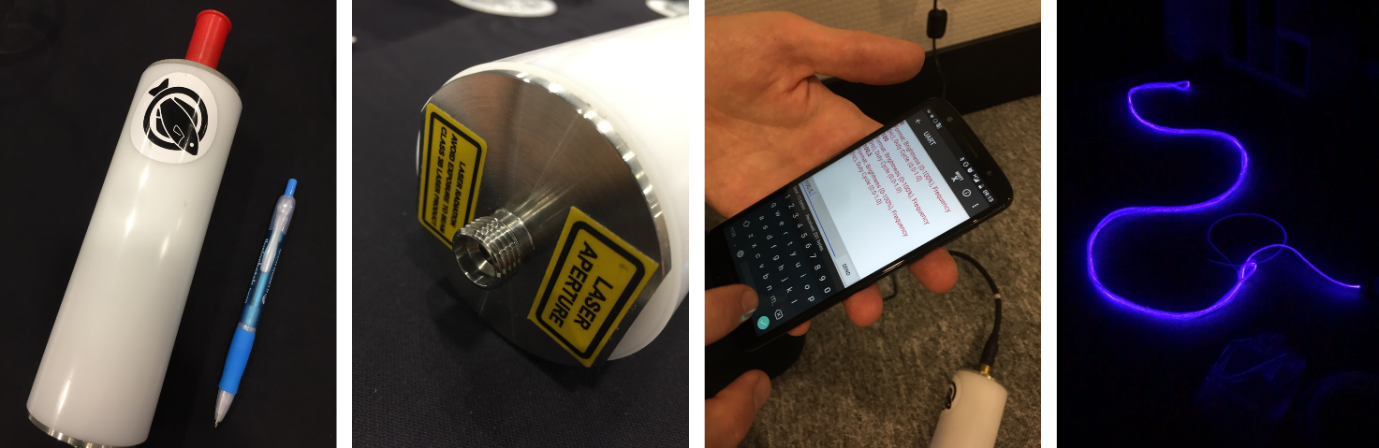

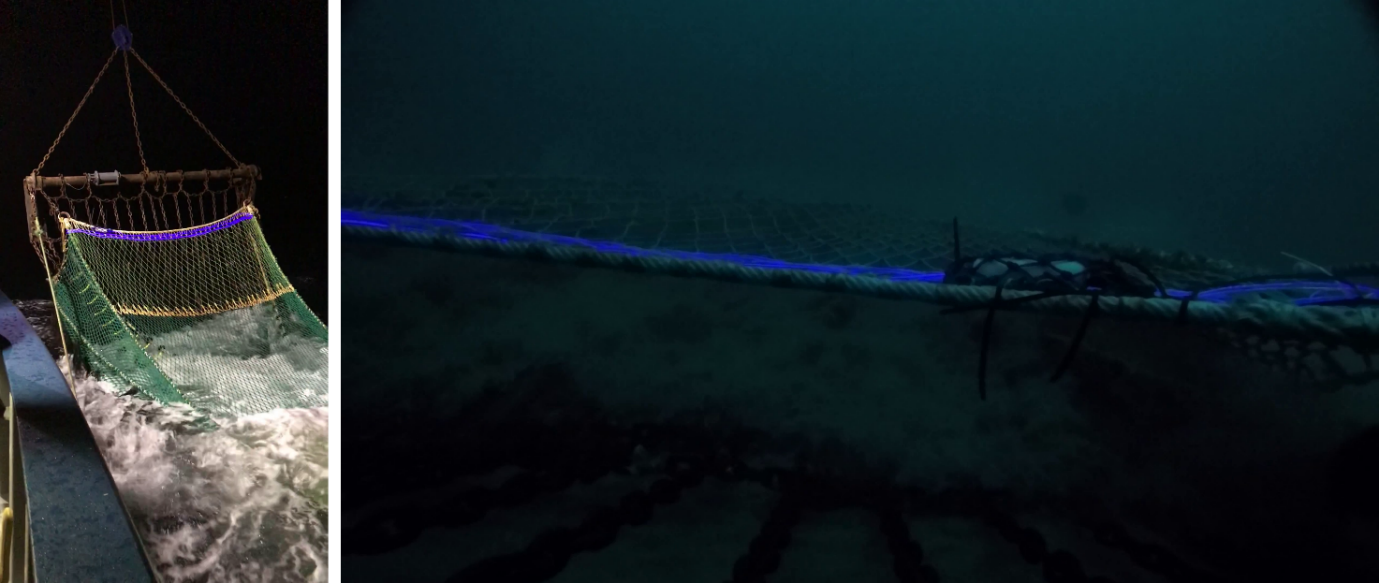

Discarding of unwanted fish catches is generally highest in bottom trawl fisheries that catch a mix of different species together. We tested the use of adding artificial lights to trawls to increase the possible escape of unwanted fish and reduce discards. Working onboard a beam trawler in the southwest of England with our project partner Interfish, and with individual skippers of otter trawlers in the English Channel and North Sea, the new SmartGear light technology was trialled in various positions on the trawls. The new technology, which can be remotely programmed to produce different types of light delivered through a flexible fibre optic cable, stood up to the rigorous test of being attached to trawls during commercial fishing operations. The experiments showed that individual species will react differently to the light output. This new technology has the potential to improve the selectivity of nets by modifying the behaviour of fish during the trawling process resulting in a reduction of discards.

Also within the SMARTFISH project, Cefas demonstrated how commercial grading machines used at fish markets can produce scientific data and are currently developing online systems that allow the sharing of information on unwanted catches with fishers so they can use it to best inform their fishing efforts such as deciding where and when to go fishing. SMARTFISH-H2020 (Innovative Technologies for Sustainable Fisheries in Europe) project has received funding from the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme over five years.

SmartGear – using lights to improve trawl selectivity

Discarding is generally highest in bottom trawl fisheries that catch a mix of species simultaneously, and for which species with the lowest quota may restrict the fishing opportunities for other quota species under a landing obligation. Installing artificial lights on fishing gear is increasingly being explored to alter the behaviour of fish during the capture process and to improve trawl selectivity. For lights to be readily accepted and used by the fishing industry, they need to be robust enough to withstand the stresses encountered during the towing and hauling processes, be versatile enough to utilise fish responses to different light configurations and improve selectivity without negatively impacting on target catches.

Light technologies were applied to beam trawls and otter trawls in the English Channel and in the North Sea in a Nephrops trawl. The technology was tested, and catches were compared from 200 fishing tows. The SmartGear tested was technically successful, but the lights have a limited effect on the main species caught by beam trawlers of Dover sole and plaice.

Cefas SmartGear project lead Sam Birch commented:

“The results of the otter and Nephrops trawl experiments were more promising, showing that light-induced a behavioural response in haddock and whiting. In both studies, increased retention of haddock and whiting were observed, and the vertical positioning of haddock was affected by the addition of lights. The light technology demonstrated the potential to change the selectivity of nets by modifying the behaviour of fish during the trawling process.”

CatchMonitor - automating catch data from video on-board trawlers

The number of fishing trips that have a scientific observer onboard to collect catch data is only a small fraction of the total fishing activity. This means that assumptions have to be made about how characteristic the data are, particularly for those catches that are returned to the sea, and for some species, the limited data will influence management decisions and restrict fishing opportunities. In recent years, Remote Electronic Monitoring (REM) has offered an additional tool for collecting scientific fisheries data, with the potential to help fill these data gaps.

See this blog by Cefas Scientist Rebecca Skirrow.

Reviewing REM data to quantify fishing activity and generate catch estimates is largely done manually by experienced reviewers and can be very time-consuming. The development of CatchMonitor aims to create an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm that automatically analyses and summarises REM video footage to provide catch estimates. This will improve the efficiency of video review, enabling larger samples of data to be analysed, releasing the full potential of REM and providing data-rich fisheries management.

Working closely with the UEA’s School of Computing Sciences team, CatchMonitor was developed using video of catch sorting from routine fishing operations. The first task was to train the algorithm to recognise and identify fish, meaning video reviewers had to generate a large training dataset, an example of annotated training images can be seen below. Once trained to recognise fish in still images, the algorithm then needed to be able to do this from a video and keep track of the individual fish to be able to count them accurately - not easy as they move along the conveyor belt. The Cefas reviewers generated data on 13,543 fish, from 5 hours of video footage from two vessels fishing in the Celtic Sea.

We started at the very beginning of this process and have made substantial progress. The performance of the algorithm was compared against results from three reviewers, with the total count of all fish, the total counts of different species and the identification of the same individual fish as points for direct comparison. For one vessel, the total counts of the algorithm were comparable to the reviewers, while the other was lower. For both vessels, the proportion of different species in the catch from the algorithm matches closely with the reviewers. For some species, the algorithm showed the same level of precision when identifying individual fish as the reviewers, but for others it was lower, reflecting the level of training data available for the different species, the quality of the images, and the density of the fish in the images.

Some visual examples of progress in SMARTFISH courtesy of UEA can be seen here – this is an example of a high fish density video footage stress test onboard mixed demersal species otter trawlers in the Celtic Sea: https://youtu.be/V0d54FnyIOk

Cefas CatchMonitor project lead Rebecca Skirrow commented:

“Overall, the testing in the Celtic Sea has demonstrated that the algorithm has come a long way and shows real promise for improving efficiency in generating catch estimates from REM. There are still improvements to be made, for example, increasing the training data set for some species to improve identification, also exploring how catches are presented to the cameras on the vessel can be modified to reduce the density of the fish in the images.”

CatchSnap - automating catch data for crab and lobsters caught by potting vessels

European crab and lobster stocks are data limited, which restricts the management options for the sustainable exploitation of these stocks. Low-cost camera systems (CatchCam) were designed and installed in shellfish potting vessels to generate commercial catch data. By applying artificial intelligence (AI) software integrated into the camera units, we aimed to identify the species, check the sex (male/female), and take size measurements of the individuals caught. These data can then be sent from the vessel to a centralised database.

The development of the technology took into account feedback from shellfish fishers, which led to working in a wider collaboration with Bangor University – who were developing a similar prototype to the one created by Cefas - and with an external company, Ystumtec Ltd. This team deployed prototype low-cost camera systems (CatchCam) on fishing vessels to obtain the training data need it to create an image analysis algorithm.

The AI algorithms are now effective in differentiating between the two species (crabs and lobsters). The images were also used to manually generate length measurements from the camera footage. The next phase of work will be to train the AI to differentiate the sex of the individuals and automate generating length data. To send and centralize all the data coming from the onboard camera units, an application programming interface (API), a SQL database, and a web application were constructed. All the elements have been tested, and the next step is to test for “live” data to be collected directly from the fishing vessel and stored.

Cefas CatchSnap project lead Silvia Rodriguez-Climent commented:

“We have made a lot of progress towards our aim to use AI trained cameras to automatically collect all the biological data needed during the fishing trips to manage these stocks. The new technology offers a game changer in collecting, transferring, and storing the information needed to improve the management of these important fisheries.”

Using fish grading machines at fish markets to collect scientific data for stock assessments

At major UK fish markets, many landings are processed using automated grader machines which automatically weigh and categorise each fish as they pass along a conveyor belt. If grader machine fish weight data are suitable to feed into scientific data collection programmes, it would provide a rich source of scientific data that is currently untapped. Working with fish market operators and market sampling staff in the southwest of England, we investigated the practicalities of collecting data from these machines - evaluating the completeness of the machine data - and compared it to data collected by our scientists in the market sampling programme.

The focus of the study was the port of Newlyn in southwest England, with additional information from the ports of Brixham and Plymouth. In total, weight data representing 1.2 million fish from 344 landings were collected for analysis. The fish length data were similar between the grading machines and scientists, and the graders provided data from significantly more landings and individual fish than the market sampling. For example, for Dover sole, data from half of all landed fish was available from the grader, whereas data from 1.4% of the landings were collected in the market sampling data.

It was observed that graders were used less often for the smallest landings (< 50kg) and some species were not sorted using the grading machines. Also, linking the landings being sorted to a specific fishing trip, and therefore information on where those catches were taken, was not always possible.

However, Cefas joint project leads David Maxwell and Joseph Ribeiro concluded:

“The evaluation shows that automated onshore market fish grader machines can be used to collect weight data to supplement the current scientific data collection for fish stock assessments. The grader machine and manual sampling have complementary strengths, grader machines produce far more samples at finer time scales, while manual sampling provides coverage of more species, better sampling of the smallest landings and vital age samples. The next step in this research is to design a hybrid sampling approach that effectively combines these different data sources.”