There is an increasing awareness that marine debris, particularly plastic, is more than an eyesore on our beaches. Recent research has shown that it could also transport species, including non-native species, large distances. Plastic has a lower buoyancy than seawater so will float, and when pushed by wind and waves it can travel hundreds and even thousands of miles before being washed up. If animals or plants that normally settle on rocks attach to the plastic and survive the transport they can be washed up with the litter in areas where they didn’t previously occur. Biogeographic barriers such as distance, depth, salinity and temperature usually prevent the long-distance movement of species, but increasingly, human activity is providing species a way around these barriers.

It sounds unlikely, but we are starting to see more and more evidence of animals from the tropics or the other side of the Atlantic arriving on British shores. Marine debris is one of many pathways for the transport of non-native species (others include shipping and recreational boating or aquaculture stock movement) but it is a big concern because it is unregulated and not well studied. With millions of tonnes of plastic entering the sea every year, this is becoming an urgent problem. Cefas is expanding the monitoring of marine debris for non-native species (some of which will become invasive species) to better understand this modern phenomenon.

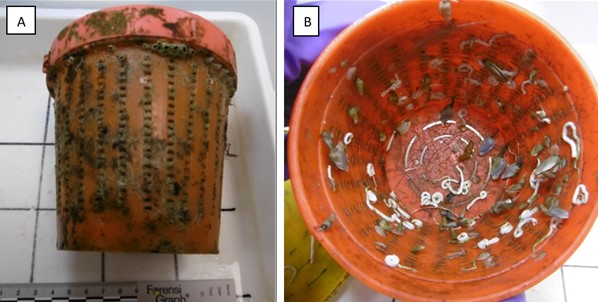

The incredible distances species can be transported this way was highlighted recently. Last October, David Taylor of the Weymouth and Portland Marine Litter Project alerted Cefas to a remarkable find on Chesil Beach (Dorset, England). Two plastic bait pots had washed up on the strandline with other plastic waste (Figure 1).

This type of bait pot is unique since it has vented sides with narrow slits. Very popular among North American fishermen, the intention is that bait is placed inside, the lid is screwed on, but the holes let the smell of the bait escape, which attracts fish, lobsters etc. The problem is that when the pots break loose, the enclosed containers provide an ideal home for anything that can squeeze through the slits, including larvae and juvenile animals. Once inside, the pot creates a perfect microcosm for animals that can feed on microscopic particles as sea water flows through it, but then they grow too big to escape. The pots also offer protection, increasing the chance that enclosed animals will survive until they wash up on a beach.

Upon opening the pots, we were met with an unexpected diversity of life (Figure 2). Among the contents were some uncommon species, seemingly transported across the Atlantic after finding an unlikely refuge inside the fishing waste.

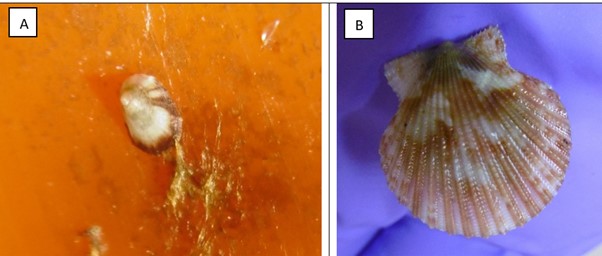

We could tell that some of the pot’s inhabitants had made it all the way across the Atlantic since we identified coastal species from the Caribbean. We have specially trained taxonomists at Cefas who identify animals and their first thoughts were that some of the animals didn’t match anything typically found in Britain. Among those that we know attach to anything floating in the open ocean - goose barnacles and keel worms, which are more often found on boat hulls - were some rarer finds such as the isopod Idotea metallica (similar to a sea-living woodlouse) which is known to be transported on floating logs or clumps of seaweed but is increasingly being found on floating chunks of plastic. In amongst these were tiny shellfish, the limpet Eoacmaea pustulata and the scallop Aequipecten heliacus (Figure 3) which occur in the Gulf of Mexico. We could only identify these exotics by consulting our literature on tropical shells, but we had a clue since these species had recently been found in Britain, again washed up on plastic debris. Still, it was surprising to see these animals alive when they washed up on Chesil Beach.

Non-native species are a concern because, if they establish, they may become invasive and can cause negative impacts where they are introduced. Even though in this case the animals in the bait pots were either open ocean or warm water species that probably wouldn’t survive for long on our North Atlantic coasts, it serves as another example of how far drifting plastic can transport animals.

“This is a great example of how reports by keen members of the public are contributing to Cefas Science and our improving understanding of how litter can transport non-native species.” said Peter Barry, Cefas Scientist.

“Working with Peter at Cefas has been eye opening. We never thought the samples we collected would contain such a diverse range of wildlife. It’s also been helpful in understanding how far marine litter can travel.” explained David Taylor, Weymouth and Portland Marine Litter Project.

Cefas is working on a way to quantify what animals are arriving, on what type of litter and on which beaches. This will help us better understand the potential risks and target monitoring where it is most needed. But in the meantime, the incident with the pots is another reminder of the need to halt plastic waste getting into the oceans in the first place, since we now know it causes another type of harm by transporting species to locations they would otherwise struggle to get to.

Read about another example of non-native crustaceans transported across the Atlantic Ocean on floating marine debris in this paper in Science Direct, Modelling of marine debris pathways into UK waters