In recent years it has become clear, both in the UK and globally, that interventions are urgently needed to protect our precious marine wildlife and safeguard the resources provided to us by the sea. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are tools used by marine managers to conserve areas of the most vulnerable or ‘valuable’ species and habitats. Human activities (such as fishing and resource extraction) are limited or prohibited within MPAs, allowing habitats and animal communities to recover, and boosting populations beyond MPA boundaries. So crucial are MPAs to global marine conservation efforts, that more than 100 countries have committed to the ‘30 by 30’ Initiative, which advocates the protection of 30% of global ocean by 2030. This ambition was initially led by the UK and is now enshrined as part of the Convention on Biological Diversity Global Biodiversity Framework targets.

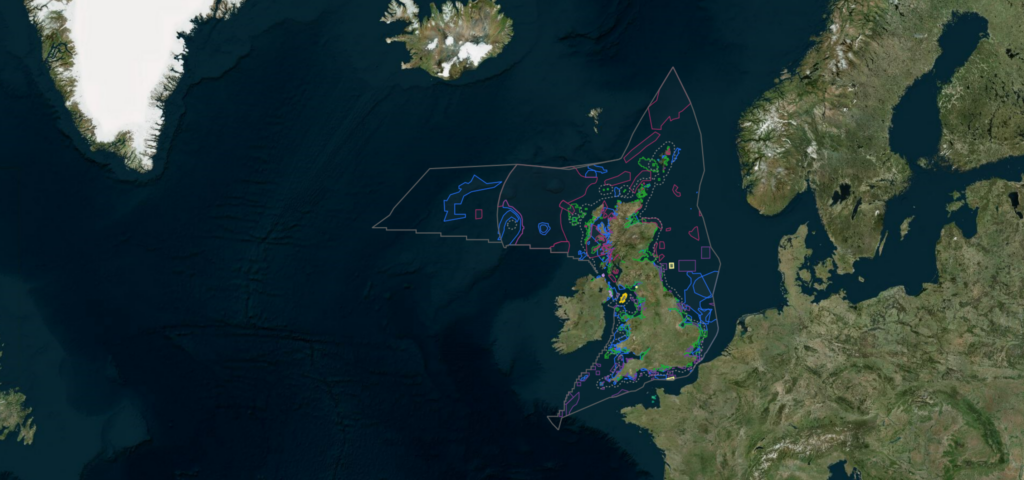

In UK waters our extensive MPA network has expanded over the last decade to include 377 MPAs, with a coverage of 38% of our waters. Surpassing the 30% designation target is an enormously positive achievement. It is, however, just the start of the UK MPA journey. MPAs are unlikely to succeed unless they are carefully managed, and their performance evaluated. Monitoring (where information is regularly collected through time) is a critical part of this evaluation process to help scientists understand whether management is leading to positive environmental outcomes. This is in part because MPAs are relatively ‘young,’ for example when compared to terrestrial MPAs where best monitoring practices and guidelines are more well established. Also, the costs and challenges associated with monitoring MPAs which can cover vast areas and a variety of different species, features and habitats can also be greater.

To try and address this in English waters, Cefas has worked closely with our Government partners Natural England and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) for almost a decade to collect and analyse initial, or ‘baseline’ monitoring data at over 60 MPAs. This baselining phase, where the first set of monitoring data is collected for future comparisons, has proved to be a rich learning experience, providing a test bed to experiment with different monitoring approaches, encounter numerous challenges, learn lessons and apply solutions to improve future monitoring practices.

In October 2023 a new paper published in Marine Policy journal, led by Cefas scientists has documented the lessons learned from 25 MPA monitoring surveys. In this paper, alongside collaborators from Natural England, JNCC and Defra, we asked: what has worked well and not so well? What could we do better next time, and what do we still need to learn to improve MPA monitoring?

One of the most crucial findings was that while national or network scale monitoring approaches are useful and needed there is also a need to treat each MPA as an individual entity in terms of survey planning, data collection and analysis, applying solutions and refining lessons at the MPA level. A good example of this concept in action is the Wight Barfleur Reef MPA. Wight Barfleur Reef is a rugged area of bedrock and stony reef in the English Channel. supporting diverse arrays of sponges, tube worms, anemones and sea squirts. Located 50 miles from the Dorset coast, covering 138 kilometres squared and reaching depths of between 25-100m, its complex geology posed serious challenges for Cefas scientists when determining how best to monitor it.

Carefully considering the unique characteristics of the reef, our scientists used multibeam echosounder bathymetry, camera elevation and imagery data to develop an MPA-specific monitoring design and camera deployment protocols (see the initial monitoring report here). Next month, aboard the RV Cefas Endeavour, our intrepid survey scientists will revisit the site to test this new approach . If successful, it will provide a new approach to collecting data on reef condition and therefore improve the quality of monitoring data from Wight Barfleur Reef. It will also be a new milestone in the moving beyond ‘baselining’ to collect a second set of data in the time series that will be used to compare the effectiveness of the MPA over time.

Another key impact of the Marine Policy paper is an agreement between the four Government bodies on where to focus research and development efforts in the future to deliver the best possible evidence for MPA success. Current and future priorities identified in the report include: developing metrics to indicate MPA condition(e.g. Downie et al. 2021), and the use of novel technologies such as improved imaging systems, environmental DNA analysis and Artificial Intelligence for improving data quality and affordability.

There is still much to do to improve our understanding and monitoring of vulnerable habitats and species in MPAs. However, reflecting on our journey so far has set our direction. Going forward, our MPA monitoring work will include working more closely across different organisations and disciplines within Cefas. We are also keen to partner with other types of survey (e.g. Highly Protected Marine Areas, Marine Natural Capital, and fish stock surveys) on the RV Cefas Endeavour to improve our understanding of wider ecosystem dynamics and challenges, as well as realising cost benefits and efficiencies. Collecting the highest possible quality data will be vital to ensure MPA management is fit for purpose. This will be important not just to hit the 30 by30 target, but to ensure our MPAs are thriving in the years to come.