The annual Invasive Species Week is taking place between the 15th and 21st May 2023, led by the GB Non-Native Species Secretariat (NNSS) with many organisations taking the opportunity to raise awareness of the issues and work that is being done to address invasive non-native species (INNS).

What are invasive non-native species (INNS)?

Non-native species (also known as alien species and non-indigenous species) are species which have arrived in a new location outside their natural range due to intentional or unintentional human actions. Most non-native species are harmless but around 10-15% spread and become invasive by harming wildlife and the environment. Limiting the spread of all non-native species limits the opportunities of one arriving which will establish and become an invasive non-native species.

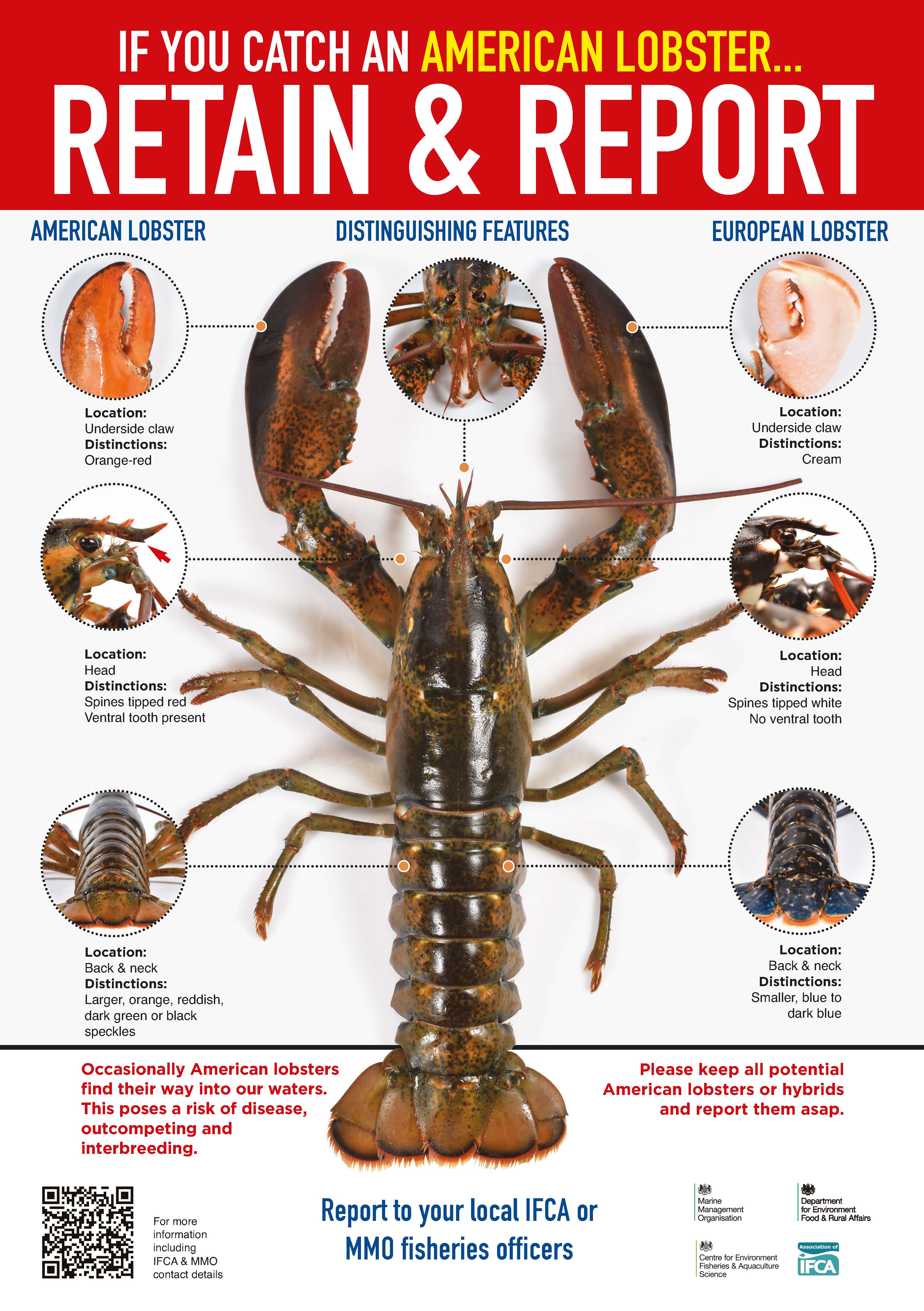

Species that are highly adaptable or from similar environments pose the biggest threat of invading. In the aquatic environment such species include goldfish, signal crayfish and American lobsters.

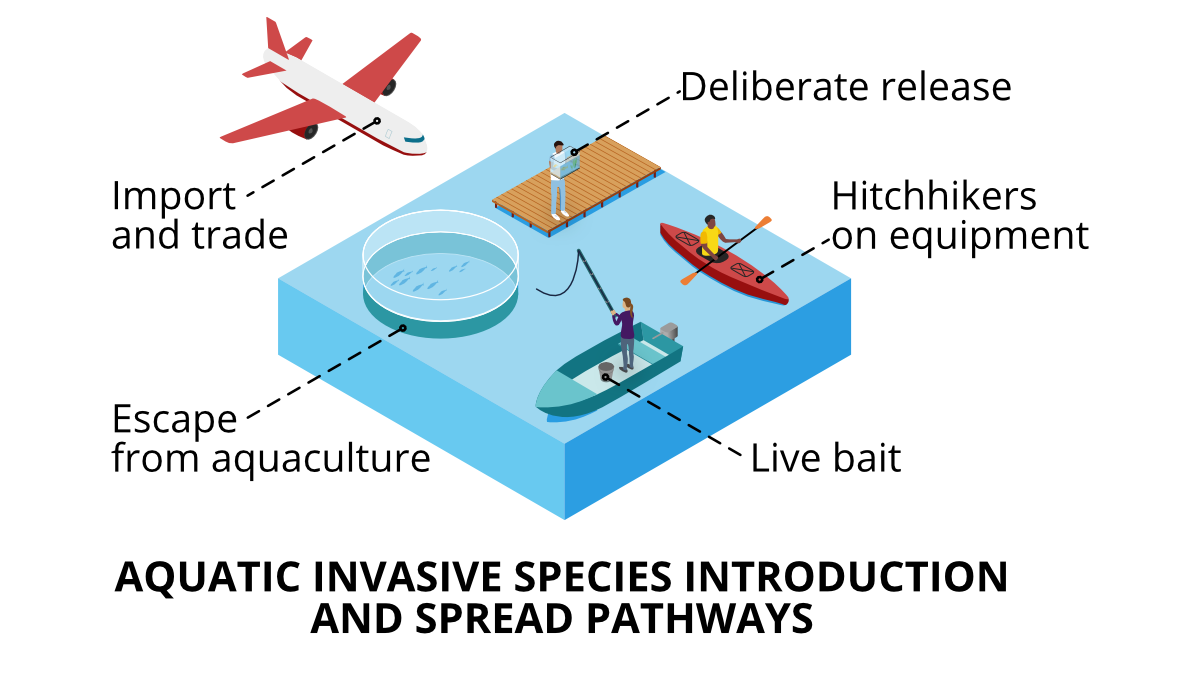

How are they spread?

The routes used by non-native species to reach new locations are called pathways. These pathways can be intentional and unintentional and include: ballast water, hull fouling, contaminated equipment such as fishing kit, dive gear, kayaks and paddleboards, marine litter, escapees from sites where they are kept, releases to the wild such as unwanted pets, illegal introductions, deliberate releases to the wild by those believing it is a positive action, hitch hikers on aquaculture stock and live bait.

Species like goldfish can find their way into the wild as live bait or dumped unwanted pets, while signal crayfish made their escape from farms in the 1980s before such threats had been realised and controls implemented. Meanwhile American lobsters can escape from coastal storage units, be dumped if unwanted or unsellable and even released by well-meaning individuals, following animal rights or religious beliefs, thinking their return to the wild is a positive action.

Why are they a problem?

As their name suggests, invaders generally cause problems and invasive non-native species have various tools at their disposal. An invasive non-native species can spread disease, prey on native species and their eggs, out-compete native species for food and habitat, damage environments, breed with native species, change ecosystems and damage equipment and structures such as waterways and pipes. They can push native species to extinction, and in Great Britain invasive non-native species (terrestrial, plant, aquatic) are estimated to cost the GB economy £1.84 billion per year.

All species have the potential to carry diseases, but some species also carry and spread diseases of international concern. Goldfish can spread spring viraemia of carp (SVC) and koi herpes virus (KHV) which can impact native species such as tench, while American lobsters can spread white spot syndrome virus and gaffkaemia which can be passed to our native European lobster, potentially affecting catch levels. The invasive signal crayfish only succumbs to crayfish plague when stressed but if they pass it on to our native white-clawed crayfish, crayfish plague will quickly devastate the population where it is introduced, which further threatens a species in decline. But the signal crayfish’s invasive toolkit doesn’t stop there, they can out-compete native species for food and habitat, further threatening native white-clawed crayfish. They can also burrow into river banks causing damage and even river bank collapse.

What is being done to prevent this?

There are a range of actions being taken to prevent the spread of invasive non-native species from international agreements such as the Ballast Water Management Convention to national legislation, eradication programmes, biosecurity guidance and awareness raising campaigns like Invasive Species Week.

Legislation has been implemented to control the use of non-native species. Controls on aquaculture ensure that potentially invasive species are only farmed in secure facilities such as indoor tanks and new species in the ornamental trade are limited to those least likely to establish in our waters. An American lobster prevention awareness campaign highlights the risk from American lobsters and encourages fishers that find them in their pots to retain and report occurrences. The Check Clean Dry campaign highlights how to minimise the risk of transferring invasive non-native species on small watercraft and fishing gear.

American lobster Retain and Report campaign

What can I do?

The simplest action is not to become part of the problem and be mindful of our own actions. Washing kit used for fishing, diving and water sports not only prolongs its life, but also limits the chances of a species being relocated to a new location, where it could invade and impact the environment as well as the reducing the enjoyment of these hobbies. Don’t leave litter on the beach as it can act as a raft, moving species many miles. Be aware that releasing an animal back to the wild because it is perceived that it shouldn’t be captive or eaten is not in fact helpful, as this may cause significant problems in the wild, often many miles from its natural home. Rehome unwanted animals rather than ‘setting them free’. Get involved with local action groups who enact control plans to remove invasive non-native species such as floating pennywort from waterways. Report sightings so that authorities can investigate and act. The GB non-native species secretariat has lots of ideas of how you can help tackle this challenge on their website.