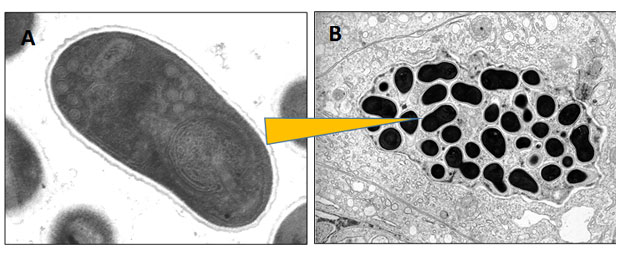

A highly opportunistic group of parasites called microsporidians can live within the cells of a wide range of host organisms - including humans.

A major infection route is by the food chain, and human infection rates are on the rise. A recent symposium - funded by the OECD’s Co-operative Research Programme on Biological Resource Management for Sustainable Agricultural Systems - focussed on this emerging threat. Specifically it looks at the role of the food chain in exposure of human populations to parasites derived from livestock, domestic animals, and wildlife.

Microsporidians are amongst the smallest known parasites. Having jettisoned much of their own cellular machinery for generating energy, they survive by mopping up the cellular resources of their hosts. This can lead to a range of debilitating diseases for the host, and in some cases, death. They are increasingly recognised as an emerging disease threat for humans.

Human infections by microsporidians are generally considered ‘zoonotic’, this is a disease that can be passed between animals and humans. They can likely be derived from hosts inhabiting both terrestrial and aquatic environments. The infection route into humans occurs by direct contact to infected animals (eg by eating a food infected with the parasite) or to 'liberated' life-stages of the parasite, which might be present in untreated drinking or bathing water.

Weakened patients at risk

Case studies indicate that human infections tend to occur in immune-weakened patients. So those suffering with diseases such as HIV/AIDS, the elderly, or people under-going cancer chemotherapy are most at risk. Prior to routine use of anti-retroviral therapies, microsporidian infections could occur in up to 85% of HIV/AIDS patients. Although prevalence declined with improved therapy, a more recent increase in newly-diagnosed cases of HIV in people over 50 years of age - coupled with an aging population of patients living with HIV - is leading to so-called HIV-associated non-AIDS (HANA) conditions that accelerate the onset of diseases normally observed in the elderly. These patients have weaker immune systems, leaving them susceptible to opportunistic infection, including by microsporidians.

The highest profile example is Enterocytozoon bienuesi – infecting gut cells of humans and an increasingly diverse array of domestic and wildlife hosts. The fact that E. bienuesi resides within a family of otherwise exclusively aquatic host parasites (fish, crabs, shrimp) provides strong support for its aquatic origins. It also raises intriguing questions about the role of aquatic hosts in the epidemiology of this infection in humans.

Lack of monitoring causing issues

Confirming emergence, or even increased prevalence, of microsporidian infections is difficult due to a general lack of monitoring. However well-publicized cases of microsporidian infections in various farmed and wild animals - ranging from bees to shrimp - and in human patients with underlying infections - such as HIV - highlight their role as general sentinels of immune health. In many cases, emergence (including potential for host switching between species) appears linked to weakened immunity.

The contribution of climate change and other ecosystem-level stressors (eg ocean acidification, intensification of farming) may lead to greater disease burden in hosts from all environments and thus increase the ‘contact rate’ between infected animals and humans. When coupled to an increasing global population of immune-compromised individuals (eg associated with ageing, cancer chemotherapy, and HIV), microsporidian infections are expected to become more common.

The major transmission route between host groups is by the food chain. Broader consideration of plant/animal/ human diseases associated with environmental pressures under the 'One Health' agenda will be increasingly required. This will address the grand challenges associated with global sustainability and to manage microsporidian infections in wildlife, food animals, and humans.

For updates please sign up to email alerts from this blog, email me or you can follow us on Twitter @CefasGovUK.